Last updated on July 3, 2024

Switzerland is widely considered to be the centre of the horological universe. Certainly today, it is the source of the vast majority of luxury wristwatches. However, this certainly wasn’t always the case. In 1800, around half of the world’s watches, about 200,000 pieces a year, were produced by English watchmakers. In this post, we take a look at the history of English watchmaking.

Early years

The years between 1650 and 1750 saw incredible advances in horology in England. Famous English watchmaking names include Thomas Tompion (1639-1713), George Graham (1673-1751) and Thomas Mudge (1715-1794). Tompion was a noted English clockmaker, watchmaker and engineer. He is still regarded, to this day, as the “Father of English Clockmaking”. He was a pioneer of improvements in timekeeping mechanisms that set new standards for the quality of their workmanship. In particular, he is credited with inventing the Tompion regulation (1674–75). In addition, he was the first (1695) to construct watches with a practical form of horizontal escapement.

Around 1712 Tompion went into partnership with George Graham, who had married Tompion’s niece. Together they made improvements to the cylinder escapement designed by Tompion, which had been patented by Edward Barlow, William Houghton, and Tompion in 1695. Graham went on to perfect the dead-beat escapement, developed by astronomer Richard Towneley in the mid-1670s. Both Tompion and Graham are buried in the same tomb in Westminster Abbey.

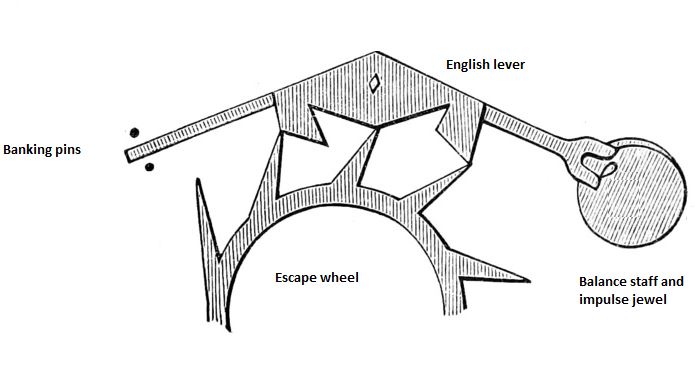

Lever escapement

Between 1730 and 1738, Graham had an apprentice, Thomas Mudge, who went on to be a successful watchmaker in his own right. In the mid-1750s, Mudge invented the detached lever escapement. This invention is considered the greatest single improvement ever introduced to watchmaking. However, it wasn’t perfected and in common use until the first quarter of the nineteenth century. It was a very accurate escapement, which was relatively easy to make and repair. It eventually superseded the verge escapement in the 1840s-50s. The lever escapement remains a feature in almost every mechanical watch made up to and including the present day.

Another significant English watchmaker of the 18th century was John Harrison (1693 – 1776). Harrison was a self-educated English clockmaker who invented the marine chronometer. This was a long-sought-after device for solving the problem of calculating longitude while at sea. Harrison’s solution revolutionised marine navigation and greatly increased the safety of long-distance sea travel. This clock was perfected after a decade of testing. It proved to be incredibly accurate on two transatlantic voyages in the 1760s. His contribution to the world of horology eventually earned him a prize of £20,000 (offered by Parliament).

Traditional watchmaking

In the 18th and 19th centuries, traditional English watches were not crafted by individuals. Instead, they were assembled by large communities of specialist workers. Watches were “made” on the division of labour principle, where individual specialists would each do one part of the work. As a task was completed the watch would be passed to the next man to assemble a different component. For example, one specialist would fit the escape wheel and another would assemble the balance wheel. However, neither specialist could do the other job. This was true for dozens of highly skilled craftsmen who made all the individual parts of the watch. These components were often made in their own workshops. It was a complex network and could only exist in the few main centres of London, Liverpool and Coventry.

English watches of this period began as a collection of components that had been roughly machined close to the finished sizes. These components were supplied to watchmakers as rough movements called “frames”. A frame consisted of the top and bottom plate. This was separated by pillars and included the mainspring barrel, fusee and the train wheels mounted on their arbors. There was no escapement or balance and balance spring, and no jewels. The watchmaker was left to source these additional components and fit them into the frames. The watchmaker had quite a bit of flexibility to produce watches of varying quality from the same rough movement. For many years the town of Prescot near Liverpool had a monopoly on the supply of frames. However, in the late 19th century frames also began to be made in Coventry.

Competition

From the middle of the nineteenth century, English watchmaking came under increasing pressure from high-quality American and Swiss manufacturers. They were producing watches using mass-produced machine-made components that were assembled by cheaper semi-skilled labour. Large amounts of financial capital were required to purchase machinery, which took years to show a return on the investment. Many of the smaller makers using the traditional craft system simply did not have the required money to make the investment.

English watchmakers also continued to use the fusée. While the fusée had served a functional purpose in the past, by improving accuracy. However, it quickly became unnecessary following the emergence of new metal alloys for mainsprings and balances. The complexity of the fusee added substantially to the bulk of the watch. It also added to the cost of making an ordinary watch without significantly improving its accuracy. However, it was still useful in watches and chronometers where very high accuracy was required. English watchmakers persisted with the fusée because they thought the public recognised it as a sign of a quality movement. The public probably didn’t have a clue what a fusee was. As a result, they were buying cheaper, slimmer and lighter imported watches from Switzerland and America.

Mass production

However, some companies were able to make the transition to the mass-produced method. These included The Lancashire Watch Company, Rotherham & Sons, J W Benson and H Williamson Ltd. Unfortunately, the Swiss and Americans had a head start and the English manufacturers were never able to successfully compete. The First World War didn’t help the cause. The J W Benson factory in London was bombed and Benson was forced to produce watches using imported Swiss movements. Additionally, much of the skill sets used in watch manufacturing were poached by the armaments industry.

Ultimately, it was the reluctance of English watchmakers to leave behind their hand-crafting customs for mass production. This would result in the gradual demise of the entire English watchmaking sector in the decades after the war. Few of these companies even lasted long enough to be affected by the quartz crisis of the 1970s. Some brands have been ‘resurrected’ in recent years by modern companies trying to cash in on a falsely perceived heritage.

See also, the history of Swiss watchmaking.

A list of additional posts regarding antique watches can be found on the Guides page.

Great article thanks. I’m hoping you might be able to help me. looking for details on the Townley family of Liverpool who were watchmakers- at least 3 generations but maybe more and were around in the 1800’s but possibly longer. I’m a descendant in Australia and am finding it really difficult to find any information about them. I’m wondering if you know of anyone who could help me with this?

Kind regards

Hi Karen,

I am also from Australia, originally from Sydney, but now living in London. I have not come across any watches made under the Townley name, however there would have been a significant number of watchmakers in the Liverpool region during the 1800’s. The UK census records are a good source of information, allowing you to track addresses and occupations per household. The census records are freely available online. The Museum of Liverpool has a horological collection and may be able to provide some information. Additionally, the nearby Prescot Museum has references to watchmaking. I hope this helps. Thanks for commenting, Jason

Hi my Grandad X 2 was James Bromfield, born in Coventry and was a watchmaker according to all the Census. In 1841 he was in King Street in Clerkenwell. His name is in the watchmakers book in 1861. He died in 1861 but I would like to find out anything about the watches that he made or anything about his occupation.

Hi Elsie, I cannot find any information regarding James Bromfield outside of the Census data. Did he work independently or was he working as a watchmaker for a specific company? What is the name of the book that you refer to? The term watchmaker has a very broad meaning, particularly in Britain. You can read about watchmakers in this post: What is a watchmaker? Perhaps, if you can answer my questions above, I might be able to help further. Thanks for commenting, Jason

I have a watch inscribed T Budbury London.

Silver pair case dated London 1727.

I can’t find any record of him on the Internet.

Can you please help?

Thank you, Jonathan Fenton.