Thomas Mudge, (born Sept. 1715, Exeter, Devon, Eng. died Nov. 14, 1794, Newington Place, Surrey), is widely considered England’s greatest watchmaker. His most important horological invention was the lever escapement, which is the single greatest improvement to watch movements ever made. The lever escapement is still in use in modern mechanical watches.

Note: there are date discrepancies with the year of his birth. It is listed as either 1715 or 1717. These dates differ across reputable sources such as Wikipedia and Britannica.

Early life

Thomas Mudge was born in Exeter in late 1715 or early 1716, the second son of Zachariah Mudge (1694-1769), schoolmaster and clergyman, and his first wife Mary Fox (d. in or prior to 1762). Shortly after the birth of Thomas, the Mudge family moved to Bideford, where Zachariah had become headmaster of the grammar school. Thomas received his early education at Bideford Grammar School. In 1730, at the age of fifteen, Thomas was sent to London by his father to commence a watchmaking apprenticeship. His master was none other than the eminent clock and watchmaker, George Graham who had trained under Thomas Tompion.

In 1738, Thomas Mudge qualified as a watchmaker and gained his freedom of the Clockmakers’ Company. He worked privately for a while, being employed by a number of prominent London retailers and watchmakers. Whilst making a most complicated equation watch for the eminent John Ellicott FRS, Mudge was discovered to be the actual maker of the watch. As a result, he was subsequently directly commissioned to supply watches for Ferdinand VI of Spain. He is known to have made at least five watches for Ferdinand, including a watch that repeated the minutes as well as the quarters and hours.

Career

From the late 1740s and into the early 1750s, Thomas Mudge worked on developing a new form of escapement for portable timekeepers; at around the time of the death of his former master, George Graham, in 1750. In fact, in that latter year, Mudge took premises at 151 Fleet Street, and on 18 November, two days after the death of Graham, he began to advertise for work on his own behalf. This marks the beginning of a remarkable career, with Mudge rapidly acquiring a reputation as one of England’s outstanding watchmakers. On 27 October 1753, Mudge married Abigail Hopkins of Oxford, who died in 1789; the couple had two sons. Also during this period, Mudge formed an association with a former fellow apprentice, William Dutton, which led to a partnership by the early 1760s, with both names appearing on their productions.

In 1748 Mudge set himself up in business at 151 Fleet Street, and began to advertise for work as soon as his old master, George Graham, died in 1751. It marked the beginning of a remarkable career, with Mudge rapidly acquiring the reputation of being one of England’s best watchmakers. Mudge formed an association with a former fellow apprentice, William Dutton, which led to a partnership by the early 1760s. The timepieces were often signed with the names, Mudge & Dutton, appearing on their dials.

Lever escapement

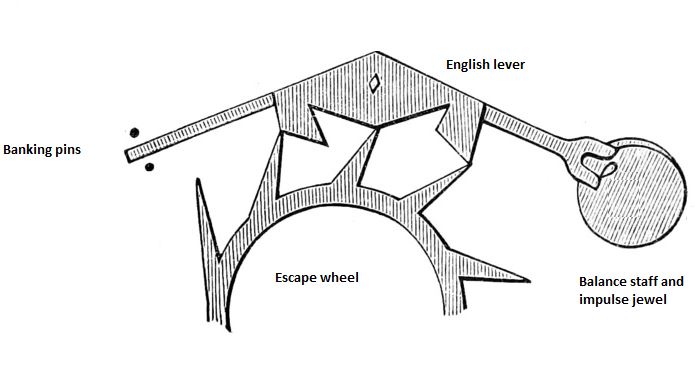

At the time when Mudge began to develop a new type of escapement, there were two escapements commonly used in watches, the verge and the cylinder. The verge escapement was robust and suited to everyday use while the cylinder was more refined and suited to more accurate timekeeping. However, both of these escapements had an inherent problem, the oscillating balance controlling the timekeeping was in constant contact with elements of the escapement. This created friction that subsequently affected the timekeeping due to wear and tear. Mudge invented the lever escapement around 1755. However, it wasn’t until 1770 that he finally incorporated the invention into an actual watch.

Mudge’s design separated the balance and escape wheels, introducing a lever between the two components to link them indirectly. This significantly reduced friction as the components were not in constant contact. The end result was a far more accurate and reliable timepiece. The lever escapement has been refined from Mudge’s original design, most notably the move to the Swiss lever escapement in the mid-19th century. However, the underlying concepts of Mudge’s invention have remained unchanged.

In 1765, he published the book, Thoughts on the Means of Improving Watches, Particularly, those for Use at Sea. In 1770 George III purchased a large gold watch produced by Mudge, that incorporated his lever escapement. This he presented to his wife, Queen Charlotte, and it still remains in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle.

Marine chronometers

In 1771, Mudge retired from active business in London due to ill health. He retired to Plymouth to be with his brother, Dr John Mudge. His retirement enabled Mudge to focus his attention on the improvement of marine chronometers designed to determine longitude at sea. In particular, Mudge was trying to develop a chronometer that would satisfy the rigorous requirements of the Board of Longitude. He sent the first of his designs for trial in 1774 and was awarded 500 guineas for his design.

He completed two others in 1779. However, the Board of Longitude were setting increasingly difficult requirements. When they were tested by the Astronomer Royal, Nevil Maskelyne, they were declared unsatisfactory. There followed a controversy in which it was claimed that Maskelyne had not given them a fair trial. Eventually, in 1792, two years before his death, Mudge was awarded £2,500 by a Committee of the House of Commons which decided for Mudge and against the Board of Longitude, then headed by Sir Joseph Banks.

Death

In 1776 Mudge was appointed watchmaker to the king. In 1789 his wife Abigail died. Thomas Mudge died at the home of his elder son, Thomas, at Newington Butts, south London on 14 November 1794. He was buried at St Dunstan-in-the-West, Fleet Street.