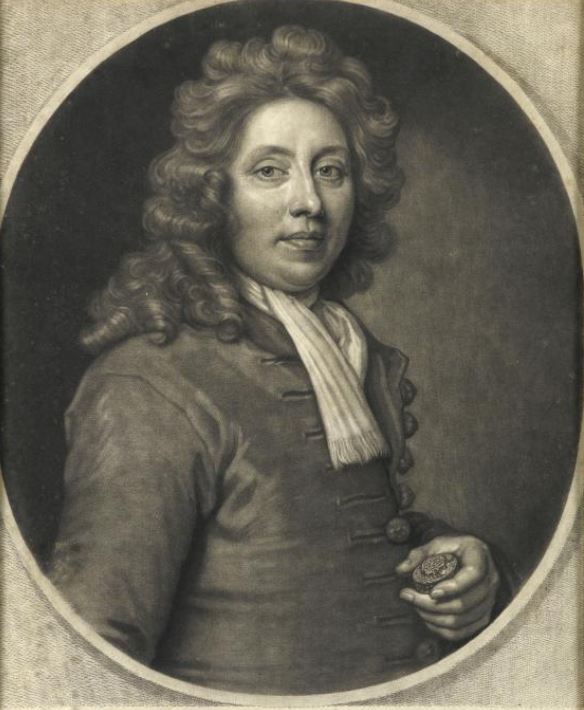

Thomas Tompion (1639-1713), has long been regarded as the Father of English clockmaking. Tompion’s work includes some of the most historically important clocks and watches in the world of horology. He was a pioneer of improvements to timekeeping, including being one of the first watchmakers to successfully apply the balance spring to watches. He died in 1713 and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

Early life

Tompion was born in 1639 in the village of Northill, Bedfordshire, England. He was the eldest son of a blacksmith, also named Thomas Tompion. In his early years, he most likely worked for his father acquiring metalworking skills. In 1664 he was apprenticed to a watchmaker in London and began his horological career. Tompion was a member of the Company of Clockmakers, in London. He joined in 1671 and served as master in 1703. Tompion remained a member until his death. A plaque commemorates the house he shared on Fleet Street in London with his equally famous pupil and successor George Graham.

Career

One of Tompion’s most important early patrons was the English scientist Robert Hooke, who invented the balance spring. Tompion’s relationship with Hooke was a key to his success as it opened doors to royal patronage and gave him access to the latest scientific advances. Tompion’s success was based on the sound mechanical design of his work and the high quality of the materials used. In just a few years after he established his own business in London, he had become one of the most renowned watchmakers in the city. When the Royal Observatory was established in 1676, King Charles II commissioned Tompion to create two identical clocks. These were installed in the Octagon room with both clocks only needing to be wound once a year. They proved to be very accurate and were instrumental in achieving the correct calculations needed for astronomical observations.

Tompion had excellent business skills and soon became the leading retailer of clocks and watches in London. In 1690, he was employing as many as 20 people at his Fleet Street establishment located at the sign of the Dial and Three Crowns. His customers were chiefly from the wealthiest classes, including royalty and the aristocracy of England and other European countries.

Partnerships

In 1701 Tompion went into partnership with Edward Banger, who had worked in the business and had married his niece. They produced watches and clocks with both of their names on the dials. However, in 1707, for unknown reasons, the partnership ended. Production continued, but with Tompion’s name alone on the dial. In around 1712 Tompion entered another partnership with George Graham, who had married another niece, Elizabeth. Graham took over the business on Tompion’s death. Graham also shares the distinction of being buried in Westminster Abbey, covered by the same stone as Tompion. During his career, Tompion produced hundreds of clocks, thousands of watches, as well as a number of scientific instruments. Such was the quality of Tompion’s work, that many of these timepieces still work today, three hundred years after his death.

Legacy

Tompions’ work with balance springs in watches was particularly important because it had the potential to be much more accurate than earlier watches. A few of Tompion’s early spiral balance spring movements had a standing barrel and no fusee. These were found to have poor accuracy due to isochronism. He added a fusee to subsequent movements and the improvement in accuracy was such that this became the standard pattern in English watches throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. He also introduced regulators to the balance spring. These allowed small adjustments to the timekeeping of a watch by making a small change in the effective length of the balance hairspring. The Tompion Regulator is named after him. It has a distinctive design in which the curb pins are mounted on a rack and moved by a pinion. The adjustments are normally made by inserting a key into the regulator and turning.

Tompion’s other works included mathematical instruments and sundials. The quality of work by Tompion set the standards upon which the 18th-century watchmakers went about their business. He wasn’t the greatest innovator. However, he was a supreme craftsman and remains a significant figure in the history of English watchmaking.