During the early 18th century it was the British watchmakers who led the way in terms of innovation and technological advances. Before that, it was the Germans and the French. However, this was all about to change as watchmaking spread across the Jura mountains in Switzerland. This was in part due to the innovative Daniel Jeanrichard, (1665 – 1741) a goldsmith, who was the first to apply the division of labour to the watchmaking industry. Prior to this point, almost all watchmaking was done in-house with a watchmaker creating the entire timepiece.

Cottage industry

The division of labour meant that the manufacture of individual components could be outsourced to individuals operating out of their own homes. This was in effect a true cottage industry. Each of these outworkers would specialise in specific components, creating them with uniform quality and high speed. It was an additional source of income for these workers and they could work indoors during the evenings and the long winter months. The completed components would be collected and taken to a central point, where the watchmaker would assemble them into a completed watch. This system was known in French as établissage. A watchmaker who works according to this system is known as an établisseur.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Swiss and British watchmaking industries were each producing approximately 200,000 watches a year. By the middle of the 19th century, the Swiss with their établissage watchmaking industry were out producing the British made watches by 10 to 1. The Swiss watchmaking industry continued to dominate the watchmaking world in turns of volume until automated mechanical systems became prominent.

However, at this time a higher volume of Swiss timepieces did not mean higher quality. Many Swiss watches would look just like watches manufactured in France or Britain, although with lower prices and wider availability. However, the quality didn’t always match up to the handmade originals. This high-volume strategy worked for a while, but was disastrous when they attempted to break into the lucrative American market. They flooded the market with cheap Swiss watches. The Americans, who were undergoing a watchmaking boom of their own, widely considered the Swiss timepieces to be ‘junk’.

Mechanised production

There were still Swiss companies still putting out great quality watches. However, they were eclipsed in number during the mid-1800s by companies churning out cheap, low-quality watches. Over in America, the mechanised production process ensured that all watches were reliable. However, the Americans lacked the historical watch-making experience of Swiss watchmakers. The Swiss quickly learnt from their mistake and adopted the mechanical production systems of the American watch industry.

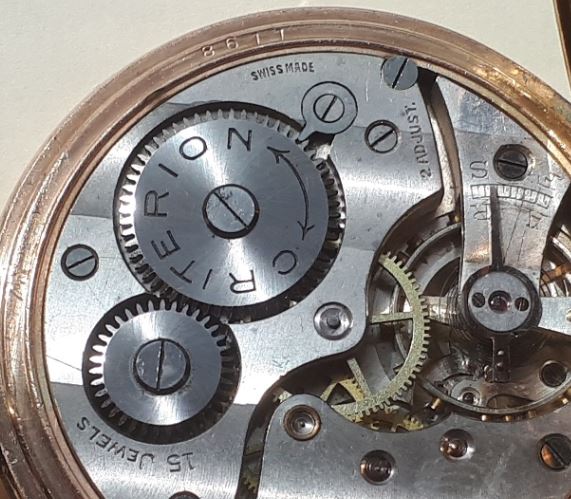

The mechanical production process allowed components to be precisely manufactured, resulting in high reliability and high volumes. This coupled with the Swiss history of quality, allowed Switzerland to return to dominate the global watchmaking market. Many of the Swiss watchmakers moved their entire production process in-house. This led to a decline in the use of the traditional établissage system. However, some of the Swiss manufacturers focussed on mass-producing ébauche movements for sale to watchmakers. Ébauche movements are essentially unbranded movements that are sold on to watchmakers. The watchmakers would then embellish the movement by polishing or branding and assemble or ‘finish’ the components into a completed watch. The mechanical production systems allowed many of these ébauche movements to be created with high quality and remarkable reliability.